You may remember the Nats latest acquisition Jonathan Papelbon from his days as the super intense, angry closer for the Red Sox. Or you may remember him from his days as the super intense, angry closer for the Phillies. All the while, he’s been one of the best closers in the game, other than maybe one season, but he hasn’t been the same guy the whole time.

The Inevitable Diminishing Fastball

So while you may remember the 95 mph fastball from his Red Sox days, those are actually far behind him. He really sits around 92 right now, which is not exactly what you’d call a blazing fastball these days. Drew Storen, by comparison, has averaged 94.6 mph this season.

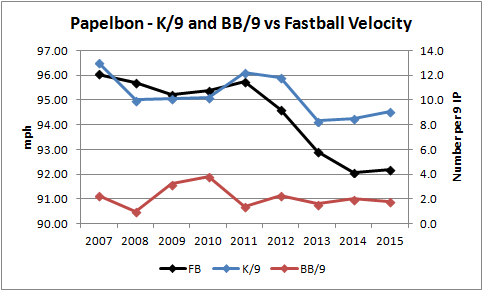

With that loss of velocity we see from all pitchers as they age, there has been a reduction in strikeout rate. Take a look at Papelbon’s FB velocity (associated with the left axis) compared with his strikeout and walk rates (right axis):

The reduced K/9 is not surprising, although the dropoff isn’t as precipitous as the reduction is velocity. It’s still a good number, in the 8-9 range. Again, comparing to Storen, this year Drew is at 10.9, but it’s the only year in double digits, and his career number is 8.5.

While you might not think the BB/9 rate should change, it’s a good indication that he a) hasn’t lost much in terms of control and b) hasn’t tried to nibble the corners more than in the past with his reduced velocity. Giving him a bit more credit, since that BB rate has gone down a bit, his K/BB rate is sitting at an enticing 5.0, above his career average.

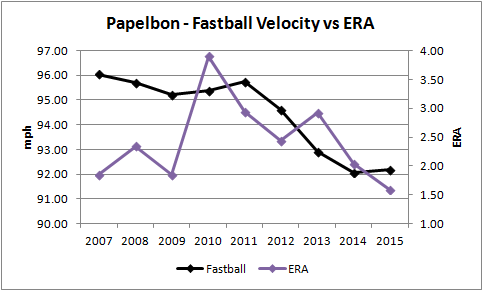

Regardless, the strikeout rate has suffered with age, so what about his effectiveness? A quick look at his ERA shows that there hasn’t been that much coorelation

Despite a drop in velocity, his ERA has gone down the last couple of seasons from a poor (for him) 2013. Another way of saying it is that he’s been as effective at run prevention at 92 mph as he was at 95. But why?

For one thing, it’s the movement on the fastball. It moves a TON – again let’s compare to Storen. Storen’s FB has a horizontal movement of -4.51, whereas Papelbon’s is -7.69 this year. That’s a significant difference, and it allows him to remain effective even without velocity, and, without as many strikeouts.

More than Just a Fastball

Papelbon’s approach isn’t, however, just about his fastball. He throws it about 3/4 of the time, the rest of the time he mixes in two strikeout pitches – a slider and a splitter. He almost never throws the slider to lefties, whereas when he’s facing righties, the splitter gets used about half as much as the more prevalent slider.

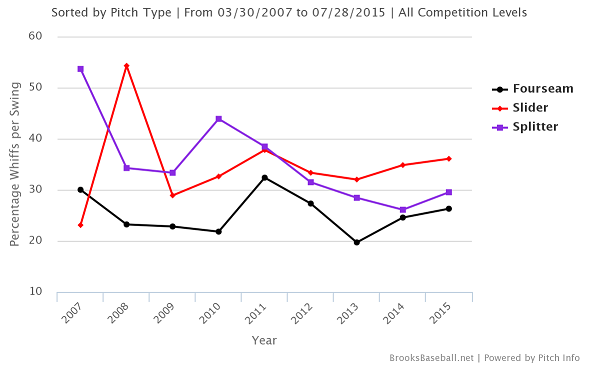

They’re both strikeout pitches, as evidenced below in the whiffs per swing chart

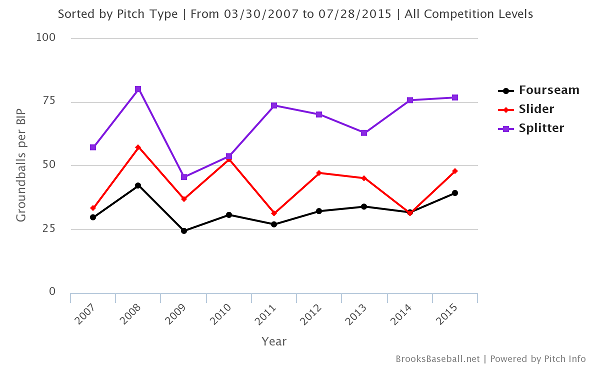

The slider is clearly a pitch he uses for strikeouts, with a whiff-per-swing rate of 35%. The splitter is also good at 30%, but neither seems totally devastating. And it still doesn’t answer why he’s been so good. The groundball rate by pitch sheds some light on that

Basically, his slider is a fairly decent groundball pitch, and it’s averaged a little less than a groundball every 2 balls put into play. Certainly a good rate when you consider about 1/3 of the time batters are swinging they can’t even hit it. But that splitter looks absolutely devastating. Between a strong whiff rate and an unbelievable groundball rate, we can see that lefties are in trouble.

Basically, his slider is a fairly decent groundball pitch, and it’s averaged a little less than a groundball every 2 balls put into play. Certainly a good rate when you consider about 1/3 of the time batters are swinging they can’t even hit it. But that splitter looks absolutely devastating. Between a strong whiff rate and an unbelievable groundball rate, we can see that lefties are in trouble.

Not surprising, then, righties and lefties have almost identical numbers against him, something that’s pretty rare for a RHP. In fact, it’s not completely identical – it’s the lefties that hit slightly worse against him, a pretty surprising fact.

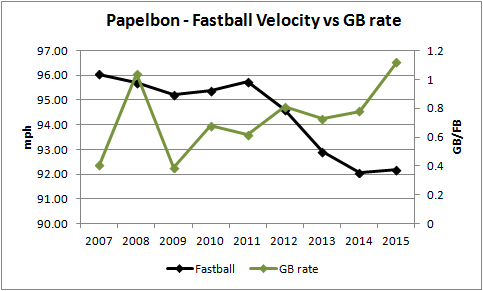

We’re starting to put together a story of a guy who used to strike everyone out, and while he’s still striking out a bunch of guys, it’s not as much. But he’s still effective. And that’s because he’s been getting more groundouts as that fastball velocity has decreased.

It’s important to remember that the GB/FB is only for those balls put into play – so thinking the groundball rate is bound to go up as the strikeout rate goes down isn’t right. Instead, as he’s lost some velocity and lost some ability to strike guys out, he’s been able to increase hitters propensity to hit grounders. And it’s been a good rate the last few seasons, even if 2015 is exceptionally (and maybe unsustainably) high.

The New Pap

Papelbon has transformed himself from the guy that helped the Red Sox win a World Series in 2007, and went his first 26 postseason innings without giving up a run. It was only in his 4th postseason, and his 27th playoff inning, that he gave up 3 ER and got his first blown save.

No, he’s no longer that super intense, angry strikeout pitcher who induces alot of grounders. Today’s he’s a super intense, angry groundball pitcher, who strikes out alot of guys.