On the wonderful Effectively Wild podcast, hosted by Ben Lindbergh and Sam Miller, they had a discussion this week about the value of free agents. It was inspired, at least in part, by a Baseball Prospectus article written by Russell Carleton about how why guys don’t get paid necessarily what they should. Essentially, the current value on the open market is around $7.5 million per win above replacement.

Both the article and the discussion were very interesting, and I won’t get into the details of them here, but they got me thinking… forgetting about the outside factors of perception, chemistry, industry and even budget limitations, is it worth it to pay these guys per WAR?

Let’s look at Bryce Harper for a second. Baseball Prospectus hasn’t published their forecasts yet for the out years, they just have the spring 2015 forecast. The numbers there aren’t worth mentioning, because after putting up a WARP (BP’s WAR) of 11.2 this season, his forecast will be completely different. So instead, I’ll just throw a number out. Let’s pretend he averages a WAR of 8.0 over the next decade . Some will say this is high, but Trout has exceeded that each of the last 4 seasons, and the number itself isn’t THAT relevant, we’re just doing a thought exercise here.

So, let’s just say he does that. By the current value of $7.5 M per Win Above Replacement, that would put Bryce at a value of $60 M per year. Or, for a 10 year contract, he’d be worth $600 M. I don’t think anyone suspects he’ll get quite that much, and if you want to know why, seriously, go listen to the podcast and read the article.

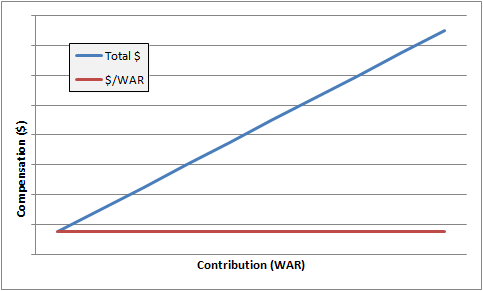

Clearly, the more WAR you bring, the more you should get paid. But it’s also a pretty safe assumption that the higher WAR you contribute, the more marginal value you’re adding to the team. This is because, essentially, it is better to have a 6 WAR player than, say, four 1.5 WAR players. If you can contain all 6 of those Wins in one guy, you can go get another good player. So it’s worth it to compensate the better players just as much by WAR as the worse players. That would look something like this:

The blue line showing the player’s total compensation, the red line is compensation per win above replacement. And that’s where you get Bryce at $60M per year.

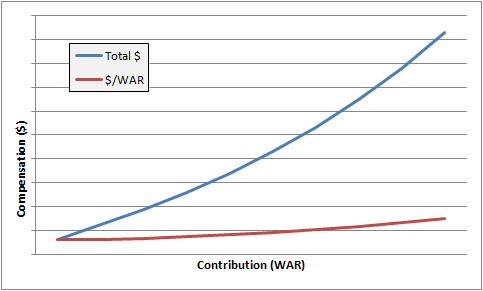

Except, that doesn’t quite work, because, by the logic of one player with 6 WAR being more valuable than three with 2 WAR or six with one WAR, the the more WAR an individual can contribute, the more he should be paid per win.

With that logic, Sam notes that it shouldn’t be linear, because a player’s “5th and 6th wins should presumably be more valuable”, which would imply that compensation vs contribution should look something like this:

This shows the recognition that the more WAR you can contain in one individual, the more valuable it is for your team. And I agree with Sam conceptually here. In this case, Bryce would actually be worth more than $60 M per year, so you’d be getting a bargain if you signed him for that…

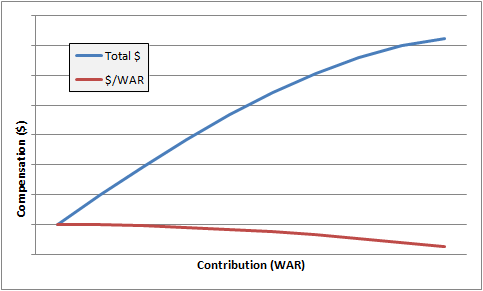

But instead, as players get better, they tend to not get additional pay for it. The marginal revenue for increasing your wins above replacement decreases. So in reality, compensation vs contribution looks like the opposite, something like this:

They go through all sorts of reasons why this is, and for the most part, I agree with them. But let’s get away from the money for a second, and talk contribution to a team.

WAR is an excellent stat, because it really is a great one stop shop to compare individuals. We know if you have the choice to play Bryce Harper or Michael Taylor, the output we’d except is different, and WAR is what it amounts to – very understandable, even if you don’t understand the mechanics.

Going back to the concept of spreading the WAR out among players or concentrating it… yes, it makes perfect sense. Except for the fact that Bryce can’t bat more than once through the lineup, and he can’t field more than one position. In a bad economics metaphor, we aren’t operating in a perfectly competitive environment. There is a strategic benefit to spreading out some of that WAR, isn’t there?

Yeah, I’d rather have a 8 WAR and a 0 WAR player because I can replace the 0 WAR player with a 2 WAR player pretty easily, and I still have the 8 WAR guy. But in a game situation, would I rather have a 4 WAR and a 4 WAR player than 8 and 0? In other words, which of these sets of players (8/0 and 4/4) would I rather give 8 player appearances in a single game? Because I’m not allowed to sit that 0 WAR guy in that situation.

If the answer is 4/4 pair, then there are implications to the value of WAR. It suggest a marginal return on WAR at a certain point. I don’t think it suggests that WAR itself should effectively be capped – that player on a one to one basis is still that much better than another player.

But the strategic implication is that just using individuals WAR to see how a team would perform, sort of doesn’t work right. It would mean that there is a diminishing return on the return you get from WAR.

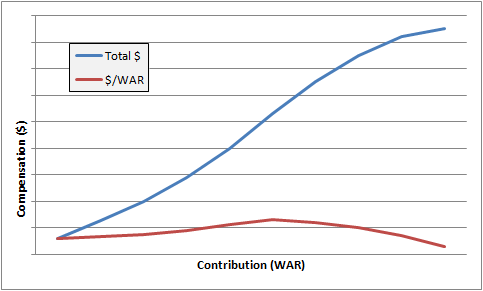

On the monetary side, it suggests a person should essentially have a limit to what you are paying them. Now, I still believe that before a certain threshold, there is more value tied up in an individual being a better player. The increasing scale for $/WAR still makes sense. But the limiting factor of ability to be used at all times might suggest at some point you are paying for WAR that you aren’t able to utilize. Is there some way to normalize the total contribution a player can make in an individual game because of his limited ability to affect that game?

I’m not sure, but if it is, then the $/WAR, with everything factored in, should look something more like this:

What this shows is that the more WAR a guy contributes, the more he should be paid per win. Until, that is, he hits a certain point. Then his contribution can’t really be felt as much, and it’s better to add wins to other players. If that’s the case, then another question would be “where is that inflection point?” Is it 4 WAR? 10? 20?

Obviously, when you reintroduce limits to the overall budget of a team, this idea becomes more likely. If this isn’t right, then Bryce is probably worth even more to a team than $50 or $60M a year, although for a variety of factors mentioned in the article and the podcast, he’d never get that much. But if it is right, he might actually be worth a little bit less than that, and at least a little bit closer to what he’ll get paid.

Ceterum censeo Bryce signarum est